Reminiscence p52

The air trip was not yet an exercise in speed. Only slightly shorter in duration than the maritime voyage (11 days against 16), the air route nevertheless went to places heretofore remote from commercial travel and gave, at least to its enthusiasts back home, a sense of new imperial unity, of “continent conscious” appreciation, in the words of Sir Harry Brittain. In aircraft that may now seem quaint or rudimentary to us, the traveler of the time flew low and slowly over African terrain. Speeds of 120 or 130 mph were the usual, and aircraft usually flew no higher than 9,000 feet (although the Atalanta, a four-engine monoplane designed specifically for the mountainous regions of Africa, could reach 10,000 feet).

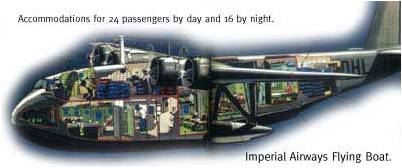

Yet with reclining chairs, tile bathrooms (a convenience of the Short Brothers Flying Boats), insulated cabins and outside air circulated through pipe systems, refreshments served by onboard stewards in some instances, comfort was assured on all aircraft in the African service. One commentator said of the four-engine Handley-Page Hannibal that the noise level was not so bad as that on a New York subway train.

These remarks fit into a broader cultural context that is worthy of comment. In 1932, commercial air travel was still primitive, particularly on the intercontinental flights that Imperial Airways made from England to India and to Africa. Such travel was characterized as frequently by mishaps as by multiple piston engines turning propellers in noisy harmony. One of the best accounts of the irregularity of such travel in Africa is found in a brief letter to the editor of the London Times from an early traveler on the Cape-to-Cairo route. The letter is one of gratitude and was titled by the newspaper, “A Passenger’s Tribute.” Published in the July 20, 1932 edition, the letter from Gerald Kayser, who had just returned from an air trip that began in Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), is a litany of major inconveniences nicely bundled in words of praise. The purpose of the letter was to commend Imperial Airways for its staff’s efficiency and “thoughtful care of passengers” on that trip.

Then Kayser explains: 1) that the pilot on the flight from Salisbury to Dodoma became incapacitated by fever and another pilot had to be flown in from Nairobi. a distance of 400 miles requiring five hours of flight time; 2) upon leaving Aswan en route to Alexandria, the next aircraft had engine trouble and was forced to return, after which the passengers were to make the journey by rail; 3) the pilot of the plane, attempting to pay for the rail tickets on his own bank account, was refused, as was the Imperial Airways representative on the spot; then, an Englishman, named Walker, provided the needed money drawn upon his own account. Thereafter, the trip went without a hitch, allowing the letter writer to conclude: “Thus the Imperial Airways triumphed over all obstacles….”

As early as December 1932, the chairman of the board, Sir Eric Geddes, undertook to make the entire trip from Croydon Airport, outside London, to Capetown. He claimed it to be a troublefree voyage (“never for one moment did the aircraft or her equipment give us the slightest anxiety or trouble…”). His conclusion was laconic: “To summarize my impressions of my journey, it was uneventful and not tiring.”

Even with the early success of such vast air routes maintained by Imperial Airways, British critics argued that the national focus on connecting the British Empire by air as it had earlier been by the famous “red line” (maritime routes) was purblind. The very name “Imperial” that clearly qualified the airline and the later choice of “Empire” as the name of the most successful series of Short Brothers Flying Boats diverted attention from the new internationalism of flight and the emergence of potentially more profitable markets, particularly those across the Atlantic. While Imperial Airways had a large network (18,000 miles to 23 countries in 1936), it actually lagged behind France, Germany and the United States in passenger air miles traveled and aircraft in service.

Imperial Airways, which had begun in 1924 as a governmentally inspired and partially subsidized amalgamation of several other airlines, is today, in its third form, British Airways, a very successful private company since 1986. The old flights of the 1930s over British dominated East African territories have given way to the more direct and geometrically configured flight patterns between London, Cairo and the Cape that are marked by contrails descriptive of 500-mph flights some 35,000 feet above the continent. At that height and speed, the African landscape is to the traveler whose vision is briefly diverted from watching a movie but a series of vast abstractions apparently without any indication of romance.

No one today would encounter the experience described in the “Contact” column of the March 7, 1937 edition of the New York Times. There it was reported that a low flying Imperial Airways plane disturbed some lions then tracking a zebra. The zebra escaped. “So angry were the lions,” the report goes, “that they not only threw back their heads and roared at the aircraft, but some of them could be seen making furious upward swings, as though endeavoring to pull down from the sky this noisy ‘bird’ that has just robbed them of their quarry.”